The invasion of Carp (Cyprinus carpio) into our waterways threatens native fish habitat, breeding and survival. Although numerous types of screens have been used to restrict the movement of fish either into or out of wetlands, most do not achieve the best environmental outcome because they do not allow the free passage of native fish and other fauna, while restricting the movement of Carp and other unwanted species.

During 2009–2010, Lake Bonney (near the township of Barmera in South Australia) received water for environmental purposes. This provided a unique opportunity to trial a wetland carp separation cage for controlling the estimated 50–100 tonnes of this species in the lake, as well as experimenting with different designs for screening fish at wetland inlets.

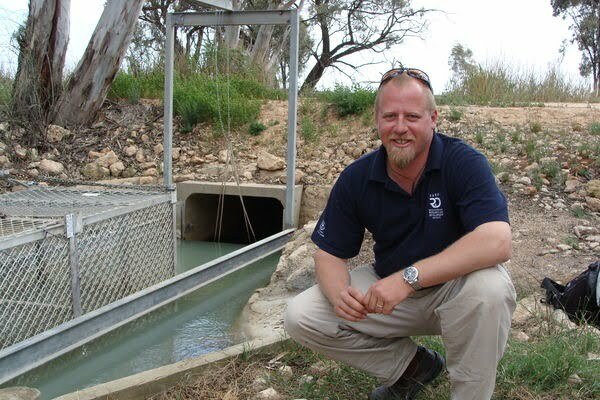

The cage and screens were designed to restrict mature Carp (250mm TL or more) from entering the lake. The cage was designed to separate Carp from native fishes using both jumping and push trap elements. The cage mesh was a vertical jail bar design with a 31mm aperture between the bars. Infrastructure mechanically lifted the cage and funnelled Carp into trailer mounted fish bins. The Carp exclusion screens were both jail bars with 31mm apertures and square grid mesh with 44 X 44mm internal dimensions.A Peterson mark-recapture experiment was undertaken after two large scale commercial harvesting events to guage the effectiveness of the harvesting on Carp populations in the Lake.

Findings:

More than 500 Carp were captured in the wetland Carp separation cage over 13 harvesting events. This was a relatively low catch rate but corresponded to an absence of any large Carp aggregations within the weir pool or inflow plume. In comparison with 2008 and 2009 years the decline in the magnitide of Carp movement was probably related to environmental factors including, earlier water allocations together with increased water temperatures and water quality within the lake. Despite this there were sufficient numbers of Carp captured to allow “proof of concept” for the cage design and operation. However, although it operated according to its intended design and function, some operational issues were observed, necessitating refinements that have resulted in a pragmatic, adaptable and safe device.

Difficulties were experienced with both screen types mostly related to the fact that they had to be installed in high flow culverts delivering about 250-300 ML per day. The grid mesh fouled rapidly consequently restricting flow and also entrained Bony herring (Nematalosa erebi) and turtles.

Although jail bars had minimal fouling, they entrained more Carp and turtles than the grid mesh. Both screen types suffered from vandalism. It was concluded that fixed screens such as grid mesh and the ‘jail bar’ design should not be used at wetlands like Lake Bonney that have high flows and easy public access, because:

- impeding Carp movement is inefficient and often obstructs native species;

- regular maintenance is required;

- they tend to deteriorate over time, and can be easily vandalised; and,

- they can compress Carp into wetlands (ie juvenile Carp pass through a screen and grow to a point where they cannot move out though the screen).

Commercial harvesting of Carp in 2009/10 reduced the Lake’s adult Carp biomass by about 33% but a significant biomass still existed in the Lake. While commercial fishing can be a valuable tool for controlling Carp, it is of limited use as a ‘stand alone’ technique – netting a proportion of adult fish does not stop Carp from spawning, and so new recruits simply replace the harvested fish.

Key messages:

This study highlights the need to tailor Carp control activities to the particular situation. Previous studies have indicated that jail bar apertures of 31mm will allow almost free passage of Bony herring. However, the mean total length of Bony herring captured at Lake Bonney was greater than previous studies indicating that a wider apertures size was required to avoid high by-catch levels (356 Bony herring in this study). Immediately there is a compromise as larger aperture sizes will allow more mature Carp through. This signals the need to survey the resident native fauna on a site by site basis prior to installing any Carp management infrastructure. Also, the motivation of Carp to migrate out of the lake decreased over time, suggesting that harvesting should occur in the early stages of the lake being filled.

Link to the final report – Proof of concept of a novel wetland carp separation cage at Lake Bonney South Australia

Related Projects:

Integrated pest management for carp at Brenda Park wetland in South Australia